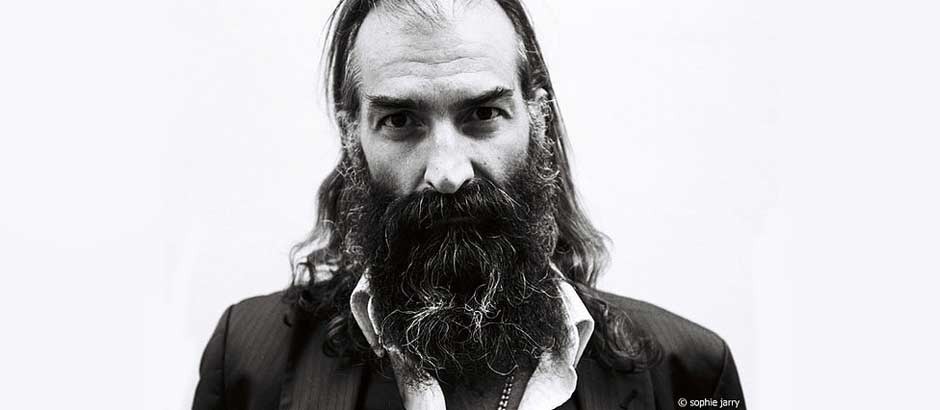

“I remember the first time I heard the Uillean pipes, I thought it was Jimi Hendrix, but it was a Finbar Furey album – amazing” – Siobhán Kane talks with Warren Ellis of Dirty Three ahead of their gig in The Button Factory on Friday.

Multi-instrumentalist and multi-faceted, Warren Ellis has always been one of music’s most interesting figures; and though he has been part of the Bad Seeds since the mid-nineties, and collaborated with people such as Cat Power, and The Triffids’ Dave McComb, worked with Nick Cave on several film soundtracks such as The Road, and released solo work over the last several years, Dirty Three remains his creative, and perhaps spiritual touchstone.

Working with Mick Turner and Jim White seems as natural as breathing to Ellis, something that is encapsulated on their records, from Horse Stories (1996), to Whatever You Love, You Are (2000) and this year’s Toward the Low Sun, the apex of their efforts after a period of writers block. And while the three men’s “unmanageable” creativity is evident on record, its true home is in a live context – something Ellis has credited with shattering that block.

Live there is something mesmerising about them, with Ellis not only providing entertaining, witty narratives inbetween songs, but by somehow morphing into a kind of shamanic presence, as much a conduit to the music as creator; yet among the high kicks and virtuoso violin-playing, there is earthy humour to be found, nestling among the reeds. They are a joy to behold live, a reminder of the impulse to connect to something meaningful that drove them towards music in the first place.

Most of their work is of course instrumental, but on “Great Waves” from their 2005 record Cinder, Cat Power sings of a sky “that spills through our mouths”, and certainly, Dirty Three remain the “dark spilling universe” – a great, big place. Siobhán Kane talks to Warren Ellis.

Around 2009 you were wrestling with a kind of writers block that you eventually overcame to create the beautiful Toward the Low Sun. Did all three of you feel that block?

We certainly all discussed it at some point, and the fact we had attempted on several occasions to record something but didn’t feel happy with the results proved it, but it was mainly related to the constraints of the group, the desire to not embellish it with other players, and that we hadn’t been able to make the time to get together as often as we may have liked.

Yes, because the three of you have the most radiant, mysterious chemistry.

I think it’s very fortunate we all operate in other areas musically and creatively, otherwise the 7 year gap in the albums would have been problematic. I would have eaten my arm off if I hadn’t done anything else. When the group started in the early ‘90’s we quickly became aware of our limitations – musically, technically and sound wise, but decided to see how far we could take a small ensemble without expanding the line up. After 3 albums it became truly challenging, but certainly what happens within the group only happens when we are this group of people. I think it’s one of the more endearing things about the group. Now after playing together more than 20 years, it feels our finest achievement is indeed remaining together as a constant line up.

It is an achievement, and I never like to measure too many things by units of time, especially because they seem to go by like sips of water – but your most recent record sounded like you reconnecting back to the beginning.

Jim and I were discussing this after a show in Tokyo – wondering why live we could find a way back into the old material, and find a new dynamic within them, and have this lead us to how to approach this recording. We had been trying to push it into more and more of a structure in the studio, and live it was always about relying on the moment, and instinct, the dynamic – live it lives or dies in the moment, and the element of risk was always something we all loved about this group, so when we realised that we decided to go into the studio with barer ideas, keeping it very minimal and opening it up. So yes, in that respect it was a return to an earlier form of thinking, but I don’t think we could have made an album like this one in the beginning. There is a certain sense of restraint and control that we just didn’t have back then. Yet I feel the same way I have always felt, until I look in the mirror. I always try to go into anything I do with the same enthusiasm, but do what is required to take it elsewhere. I don’t deliberately try to be a certain way.

Yet there is also looseness to this record, amid the structure, Jim seems even freer, somehow.

The first 2 songs were as they were recorded – I said to Jim that I was going to play something, and just go for it, and for him to, also, and we did – they are first takes, it was certainly great that he opened up his style of playing. Dirty Three is the only group I’ve seen him play in where he has this kind of freedom, but that’s the pearl when you lay out the blueprint for something.

The notion of freedom seems to permeate your work – has it always been a concept that you return to?

We have never been freeform, but we are open to everything – all ideas get a look in. So in that respect there is a freedom, and we each get to do what we want. As the group developed, our roles became more defined – there is always a base, a melody, and a form. There is always some sense of structure amidst the chaos. I love this about the work of Alice Coltrane, also.

There is a kind of freedom in you mainly being an instrumental band, giving the listener a certain kind of private space, but you seem drawn to both word-driven narratives, as well as instrumental, perhaps there is a certain common aesthetic that appeals to you?

Instrumental music can be just as guilty of the same crimes as songs. I have always liked both forms. I like that instrumental music allows the listener to bring their own stories to the table and engage in that respect, you become a bigger part of the whole picture. I also like the mysterious aspect of instrumental music, how it can appeal to base emotions without spelling things out. Sometimes you don’t want to be railroaded with someone else’s grief at the expense of your own, but the seemingly mundane can often take on epic proportions, at least in your own thoughts.

I love words, also, but find that sometimes you don’t really want to be berated by someone else’s experiences or thoughts. It blurs the boundaries between what’s theirs and what is yours. Although I am frustrated that I am not reading at the moment, I’m in a van touring and I can’t read under those circumstances, but I’ve been listening to Neil Young’s Americana, and Deep Purple’s In Rock and been watching a lot of movies, and getting through Homeland. I’m looking forward to the next season of the French series Spiral, and I just watched Enter the Void for the hundredth time – what a film!

The live aspect of your work is your touchstone, and you are incendiary live, but sometimes it feels as if the music is passing through you, that you are possessed by something greater than the sum of your parts – does it feel like that quite often?

I’ve never tried to understand that side of things, I’ve always been superstitious, and I also never watch live recordings, I’d rather remain ignorant about that, but live is the place we started playing, and it’s where we developed our language – it was always about the live thing. Studio time seemed like a chore to me and I didn’t want to evaluate things in that way, having to make decisions based on revision. I liked that the live show was unique, one off, and a moment. I’ve always loved that about it, it’s what got me into making music. As you say it is a touchstone for the group, and as I have mentioned it’s what got us back into the studio for this new one.

I appreciate going to shows where it’s about the performance as much as the music, I like the whole spectacle of it – Iggy Pop is the consummate performer and knows when to put it away.

You seem to thrive on risk-taking, and I did wonder if in part your collaborations in what might be seen as more “traditional” bands, such as The Bad Seeds had influenced you to some extent, but to the extent that you then go away and respond to that more traditional process?

When I joined the Bad Seeds it was a massive learning curve. To be in a large band means what you don’t play is as important as what you do. It’s about finding a place. In Dirty Three I don’t think I had ever stopped playing during a song until the early 2000’s. I realised I’d never stopped my bow, there was always something going on. But all the different things I have done since then have really informed how I play, and therefore inform Dirty Three. I can notice this with the other two. The work they do outside the group has been to our advantage.

You said that after the epic, wild rain storm at the Meredith Music Festival around 2004, things were so tricky and tense that you played “like your lives depended on it” – but you always seem to play like that.

No matter what the circumstances you always want to play as though this could be the last time. It seems to be the essence of the moment that’s happening on stage, when it’s a good night. I think it’s the thing that I find addictive about playing live, that each moment is unique as opposed to the studio, where you are forced to make objective decisions. I didn’t like being in the studio until 2004 when I worked on The Proposition. I think the idea of working for something else, and an image, necessitated the need to be more critical. And it was so much more an experiment in the unknown. I’d never worked for anything else before, other than a group’s vision. But the soundtrack work imbued me with a new sense of freedom I had not anticipated.

You worked as a schoolteacher for a little – though I feel like you still teach in a way. What was that experience like?

The kids were great, but the institution was a drag. I have the greatest respect for our educators, but it wasn’t for me. I’m lucky they weren’t doing tests like they do for sportsmen in those days or I’d be like Lance Armstrong.

When you were a child, you initially played the accordion after finding it in a bin, but at school there was a chance to play violin, and you said that once you saw all the girls put their hand up, you did also – in the hope you might get to spend more time with them, but it ended up with you having lessons with another boy who “thought he was a martian”. I know that wasn’t exactly your hope, but it seemed the more true, funnier thing to happen – I wonder whatever happened to that boy?

I’m not sure, he got into progressive rock in the ‘70’s. He was the local troublemaker, and I had sworn to cut down a local lady’s cactus, and he turned up at my house to watch me do it. Parents didn’t take too kindly to his presence for some reason. The last time I saw him he was driving an old Mercedes with a nicotine-stained moustache and rolled his own smokes. I believe we were both inebriated and he still had that pointed ear that he passed off as his martian heritage.

You have a kinship of sorts with Ireland, and I wondered how far has Irish music, in terms of more traditional music, perhaps, framed any of your work?

I tried my hand at Irish fiddle playing, but the lyricism escaped me. The bowing was never something I could get a grasp on, but I love folk music in general. I’d say this has influenced me as much as rock music and jazz. I spent time in Scotland and Ireland busking, and learning tunes in the late ‘80’s, but the booze got the better of me. I remember the first time I heard the Uillean pipes, I thought it was Jimi Hendrix, but it was a Finbar Furey album – amazing.

You worked with Dave McComb of The Triffids, as part of The Red Ponies – what was that experience like? He died so young, it was so sad – he had such talent. Sometimes life is so incredibly unkind.

I guess that’s life…when Dave died it was so surreal, because at that age you feel immortal, and death just doesn’t fit into the plan, so there was a sense of denial about it happening. I’d been speaking to him an hour before the accident [McComb was involved in a car crash and died a few days later, at 36]. I was very fond of him, and still miss him in that way you do when someone slips this mortal coil.

Your solo record Three Pieces for Violin was beautiful and soaring, what was that experience like?

I just recorded it and Mick put it out. I made it for a theatre piece. I have done some other solo work, but I find its appeal limited. I like playing in a group. It’s the big attraction for making music to me. I can work on a soundtrack or ideas for an album on my own, but it’s when I get with other people that the ideas take flight

Dirty Three records always seem to have a basic structure, which your inherent wildness looks to push and pull the limits of.

It is just that – a basic structure. We have always had that. If you know our pieces, you can recognise them live – we were never a random freeform act.

You have collaborated with so many people including Chan Marshall and Will Oldham – two people who use their voices as a real instrument. What have some of your most interesting collaborations been?

It’s always an honour to get in the studio with all the people I play with, it feels like they bring out the best in me, and the element of trust allows risks to be taken. Hearing Marianne Faithfull and Bryan Ferry coming through the headphones in the studio was indeed breathtaking for a kid from an Australian country town.

In terms of that country town – I remember you saying that to be in an instrumental band in Australia, when you were first starting out, was enough to get you “kicked out of town”, or kicked, anyway.

I guess we were a kind of queer proposition in the early days. Somehow we found our home amongst the rock and roll crowd. We were given a few jazz gigs and fired immediately. A blues club booked us for a 3 month residency and we lasted one set. The lack of vocals seemed to set us apart and queer the pitch, but it always seemed we were more from a place that say, country music came from – simple pure emotions. People needed to see us live I think, to get where it was coming from. There was no plan for the group in the beginning, it was pragmatic. A friend offered me a show, I knew Mick and Jim, and we rehearsed for an afternoon in my kitchen, and then played that night. There was no PA, the room was as big as a living room, and none of us could sing, so the direction was clear. Very quickly we realised we had found a space in which we could all operate, and the fact that people knew very quickly where they stood with us was an indication we were doing something right. I haven’t lived in Australia for years, and I imagine things have changed, but I grew up inland, in a tough country town, where Saturday night’s sport was cruising around town hanging out and beating people up. I had no idea what cities were about, but certainly the men still pick up the tools, don aprons and cook the bbq.

Josh T. Pearson interviewed you a few years ago, it was a really insightful, funny piece, and you seem to share a common ground in terms of truthful melancholy – Josh seems to see things as they are, but also see things as they should be. How did your friendship first emerge?

We met in the early days of Lift to Experience; we were on the same label [Bella Union]. We arrived in Denton [Texas] amidst a thunderstorm and downpour of epic scale, and we were playing in a tin shed which was dripping with humidity. There was as they say, something going on. Three guys appeared before we played, and were kind of in their own place. They introduced themselves as being from Lift to Experience and we were going to be label mates. They were intense and seemingly off the planet. I later found out they were all tripping. It was a great night.

What other projects have you got coming up over the next while?

There’s a bunch of stuff in the can. Some I can’t speak about as yet, but the soundtrack for the West of Memphis feature, directed by Amy Berg is coming out Christmas Eve, and Lawless just passed through the cinemas. My next thing is to stick on the beard and play the fat guy in the red suit for my kids.

Dirty Three play The Button Factory this Friday with Zun Zun Egui. Tickets are €23 from http://www.tickets.ie/umack & Sound Cellar.